I hear it often from power boaters, nothing ever matches. The compass says one thing, the GPS says another, and the autopilot heading is different. Which one is right? My answer is usually all of them to some degree, but when in doubt, trust the GPS/COG heading. Why It's a math thing assuming you have a decent fix, and you can check on that. The magnetic compass in the dash, as well as the autopilot digital compass are actually more prone to give you a wonky readings due to a variety of environmental factors.

I'll start with the venerable magnetic compass. This is old, very old technology that works perfectly as long as it's in a wood boat with no ferrous metal, or electrical wiring. Truth be told, this is rarely the case, and here is a simple example. The boat builder installs the compass that came from the factory perfectly calibrated. Also installed within inches is now a chart plotter, wiring harnesses, and even a nearby storage compartment to keep your steel screw driver, and hook pliers in. Calibrated it may have once been, but now no longer.

I took this picture with the chart plotter, and the batteries turned off. The heading on the compass is 195 degrees.

With the chart plotter and batteries turned on the compass heading changed to 189 degrees. Six degrees of change. Mounting the compass further forward would have reduced this impact. This designer however put a lot of effort into molding a raised spot on the console so it would look pretty. So that's where it now lives in not such a good place.

I'm sure the console full of gear including the lunch hook with the chain in the bucket isn't helping things either. So do we now trust this device this for precise critical navigation? No, but generically it's okay if you're thirty miles out in the Gulf of Mexico. Any easterly direction will find the Florida coast, somewhere, sometime.

Now how about the high tech solid state digital compass your autopilot is using. It has to be better doesn't it? Yes, maybe or not so much. On the whole if the compass is installed in the right place, and properly set up will be very accurate. Certainly I would generally trust a well set up autopilot compass before I would trust an uncalibrated magnetic compass, which is most of them.

"If" is the operative word here for the auto pilot compass. Like all compasses, the bucket of chain will affect them, along with electrical wiring carrying currents. It is a compass, it just does not use a classic magnet.

I think I hold the Guinness record for turning circles in Sarasota Bay setting up autopilots. Zen is the term I use when doing the autopilot compass calibration. Slow turns to the right, not too fast, and not too slow, and you do it for as long as the computer wants you to. You're done when you get a message. This typically says you failed, or you passed. What happens while you do these turns is the compass computer is measuring the deviation caused by ferrous metals like the engine, and electrical fields. It's in effect making an internal compass deviation card. So you passed, does this mean your autopilot compass is now perfect? Most of the time it is really close, but sometimes it's not perfect.

Here is what happens when you have "Heading Data" from an electronic compass coming into you chart plotter. It hijacks your little ship's icon orientation, and the heading line if you're using it. In addition with some systems, if you're stopped, or traveling very slowly the heading data can also hijack the chart orientation. The chart orientation while underway however is usually controlled by the GPS's mathematically calculated course over ground.

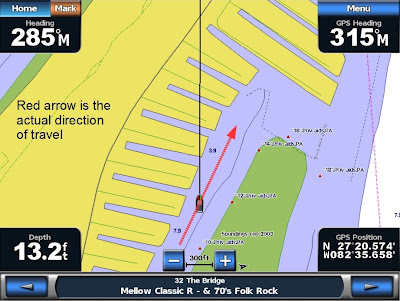

Above is an extreme example of how screwy things can get. The auto pilot compass had just been relocated. and the boat was being taken into the bay at idle speed (no wake zone) to re-swing it.

In our little graphic we have a boat on the right that is using course over ground to manage vessel icon, and the assocoated heading line direction. We are also in heading/course up mode. Our boat on the left has heading data coming from an electronic compass that is about 30 degrees out of kilter. The result is that although the two boats are traveling in the same direction, and the ship's icon is in the right position, you get a wonky effect. The ship's icon, heading line, and radar overlay if used will be twisted 30 degrees.

These are exaggerated examples, but having a electronic compass more than a few degrees out of whack can be visually disconcerting.

Course over ground, although precisely calculated has it's own display idiosyncrasies. Your GPS is continually calculating the boats position. You were there, and now you're here. The math gets done, the chart orientation, bearing and position is updated, and we do it again.

There is a small issue in all of this. There are tiny errors that creep into the system. The first is even if your boat's hull is cast into a concrete block and sitting on a precambrian shield rock face, your position is never exactly the same on each GPS cycle. Rounding of numbers, and the HDOP (Horizontal dilution of precision) vagaries will invariably shift your position a bit. You're here this time, but next time you're a inch, or three feet away, and you haven't moved a millimeter.

Now consider the speed, and source of the navigation data. The GPS data transmission rate can vary from NMEA 0183's now seemingly glacial 4800 bps to the fifty times faster NMEA N2K, and position calculation cycles vary typically from once a second to ten times per second.

In the real world, you don't want to see your chart jerking and shifting on each position fix cycle, so algorithms average out this data to make the motion smooth to your eyes. Depending on the age and speed of your chart plotter you can see the COG delay as you make a hard fast turn. The chart rotation can have difficulty keeping up, and will lag behind the ships actual orientation. Don't worry about this. During normal navigation the gear is fast enough to make all of this transparent to you.

Course over ground, although precisely calculated has it's own display idiosyncrasies. Your GPS is continually calculating the boats position. You were there, and now you're here. The math gets done, the chart orientation, bearing and position is updated, and we do it again.

There is a small issue in all of this. There are tiny errors that creep into the system. The first is even if your boat's hull is cast into a concrete block and sitting on a precambrian shield rock face, your position is never exactly the same on each GPS cycle. Rounding of numbers, and the HDOP (Horizontal dilution of precision) vagaries will invariably shift your position a bit. You're here this time, but next time you're a inch, or three feet away, and you haven't moved a millimeter.

Now consider the speed, and source of the navigation data. The GPS data transmission rate can vary from NMEA 0183's now seemingly glacial 4800 bps to the fifty times faster NMEA N2K, and position calculation cycles vary typically from once a second to ten times per second.

In the real world, you don't want to see your chart jerking and shifting on each position fix cycle, so algorithms average out this data to make the motion smooth to your eyes. Depending on the age and speed of your chart plotter you can see the COG delay as you make a hard fast turn. The chart rotation can have difficulty keeping up, and will lag behind the ships actual orientation. Don't worry about this. During normal navigation the gear is fast enough to make all of this transparent to you.

If your COG, electronic compass heading, and magnetic compass all exactly agree, it's the Christmas miracle.

In general they should all be pretty close, but in my experience rarely perfect. Three different sources of information, all operating at different updates rates will not oft exactly agree.

What I look for is are they in general close to each other? You get to decide what is close enough. My standard is more than 5 degrees out of sync on a regular basis between COG and the electronic autopilot compass should maybe given a closer look.

What I look for is are they in general close to each other? You get to decide what is close enough. My standard is more than 5 degrees out of sync on a regular basis between COG and the electronic autopilot compass should maybe given a closer look.

Here is a way with an auto pilot to take a closer look at any potential errors. On a calm open water area set the auto pilot on a north heading, check your wake to make sure it's nice and straight, and note the difference between COG, and the other two compass sources. Write this down. Do the same for east, west, and south. This all brings me back to the fact that I trust the GPS's COG data on a boat before I trust the compasses. Using COG as the baseline you should be able to see what magnitude of error the magnetic console compass has relative to the COG data, and the same for the autopilot compass.

If the autopilot compass in all four compass quadrants is off by about the same value, you can in most systems manually fine tune the heading to more closely match the COG. If the values vary notably you can try to re-swing the auto pilot compass to correct this. As mentioned before, sometimes your auto pilot compass can pass its calibration test, but still suffer from some deviation issues. If you still have deviation issues, there are two options at this point. Relocate the autopilots compass and try again. Or if the deviation is minor, know where it is and just live with it.

Now for the ships magnetic compass. If it needs calibration you can hire a professional to calibrate it. Most compasses have an internal variation on Kelvin's Balls. Calibration will result in a compass that will be as good as it can be, and you will get with it a deviation card to tape to the console that will provide the needed heading corrections.

Let's see, my bearing is 300 degrees, let me look at my deviation card. Hmm, it seems I have to steer 302 degrees to do that. A few final words about compasses. The first is I would always want to have one on a boat, along with its buddy the paper chart. The second thing about using a compass for precise navigation is it's really helpful to know where you actually are when you try to use it. Try to keep that in mind that when the chart plotter's fifty cent fuse blows.

Two last last small notes. Most (I didn't want to presume) sail boaters already know that the COG often at times does not match the compass heading because the bow can be pointed in a different direction from actual travel. They should drop the sails, and check their compasses on occasion to make sure everything is copacetic. They too can have the metaphorical bucket of chain in the wrong place, and deviation issues.

Chart orientation via heading data details vary from manufacturer to manufacturer. If you're in doubt about how all of this works on your specific system, call their tech support department and ask. This discussion is a generic amalgamation of several system's operational characteristics, and does not represent any one particular system or manufacturer.

The photo of Kelvin's Balls is is a redacted version taken by Wikipedia user RAMA.

The Raymarine autopilot head photo was borrowed from their media library.

Let's see, my bearing is 300 degrees, let me look at my deviation card. Hmm, it seems I have to steer 302 degrees to do that. A few final words about compasses. The first is I would always want to have one on a boat, along with its buddy the paper chart. The second thing about using a compass for precise navigation is it's really helpful to know where you actually are when you try to use it. Try to keep that in mind that when the chart plotter's fifty cent fuse blows.

Two last last small notes. Most (I didn't want to presume) sail boaters already know that the COG often at times does not match the compass heading because the bow can be pointed in a different direction from actual travel. They should drop the sails, and check their compasses on occasion to make sure everything is copacetic. They too can have the metaphorical bucket of chain in the wrong place, and deviation issues.

Chart orientation via heading data details vary from manufacturer to manufacturer. If you're in doubt about how all of this works on your specific system, call their tech support department and ask. This discussion is a generic amalgamation of several system's operational characteristics, and does not represent any one particular system or manufacturer.

The photo of Kelvin's Balls is is a redacted version taken by Wikipedia user RAMA.

The Raymarine autopilot head photo was borrowed from their media library.

Thanks. I am a recently retired professional airplane driver now live aboard sailor. Sailor lore seems to be that the GPS system is a tool o de Debel that will crash one's boat into land at the first opportunity; better to trust a paper chart and a compass. Unless one in an absolute expert in all things compass, interpreting paper charts, and visualizing a real live picture in ones'mind of what those two things are trying to tell you, beliving a compass fix is better than a GPS fix is a complete fantasy. A "good" compass fix will set your position within a couple of hundred feet at best, more like a couple of hundred yards. The GPS will set your position within a couple of meters. A compass and paper chart is what you fall back on when everything else goes bad. A paper chart and the most basic of hand held GPSs to give a lat / long vix would be better.

ReplyDeleteTJ, I agree completely. There is a lot of Shintoism out there which I define as worshiping the way your ancestors did navigation,. BTW I really enjoyed reading your OTR blog. I have my own equivalent, but I haven't acquired a set of Kelvin's Balls big enough to attach my name to it... yet.

DeleteHaving a steel boat with a Ritchie Globemaster inside the steel-sided pilothouse, I'm used to playing with my amusingly named "compensator balls" (Kelvin's balls is new to me).

ReplyDeleteI have made a rough deviation chart by going on a known bearing to a landmark and then going back to Start and doing a 90 degree turn and repeating until I can see if I have serious compass deviation. Currently, I haven't, but if I put the wrong gadget too close to that big compass, or forget leaving a visegrip behind it, I'm in trouble.

I run a fluxgate and a plotter and look at the Ritchie, minus the local variation. If I get within five degrees, I feel I'm doing well, because I can't hand-steer much better than that.

Rhys, the Kelvin part of the balls is Lord Kelvin, aka Sir William Thompson. I stumbled upon an interesting history of the compass compilation of his written between 1874 and 1879. By 1880 his balls were so big he patented them. Here is the link

Deletehttp://zapatopi.net/kelvin/papers/terrestrial_magnetism_and_the_mariners_compass.html

I know it's cheating but I got so upset at compasses and wandering autopilot courses a few years ago that I threw money at a Furuno SC-50 GPS compass. Best money I've ever spent. Now when the autopilot goes to a new course, it gets there precisely and without weaving. When you want to swing your magnetic "backup" compass, you can do it even in harbor as you swing around a mooring. It's a miracle!

ReplyDeleteTom, you win the battle of the compasses. It is a very impressive piece of gear, and after reading the specs I now believe it provides close to perfect heading data under all circumstances. The $3600 is an ouch, but never the less it appears to be worth it given the the quality of data it's sending. It's an IMO approved heading device to boot. Thanks for pointing it out.

ReplyDeleteI had a customer who purchaced a new to him boat that wanted to get me to set up the autopilot. I checked out the original install and all seemed well but the heading was out about 40 degrees.

ReplyDeleteI took it out and did the circles from hell and achieved deviation just on the edge of acceptable. I fine tuned the heading to align with the compass and GPS course and the AP was working acceptably.

When I got back to his slip, I was just about finished and was just packing up my tools when I did one last check of the system. The heading was now about 40 degrees out in the opposite direction than originally. I took the boat out again and did more circles and achieved a deviation that was a little better than the first time. Once agin I aligned the compass, heading and GPS course and the autopilot was working well.

I got back to the dock and just before I left, I did one more check. The heading was out 40 degrees again. While scratching my head, wondering what was going on, the cutomer noticed that whenever I went forward into the V-berth, the heading would change.

Then I finally found the problem. The boat manufacturer had used strong rare-earth magnets to hold the V-berth doors open and closed. The magnets were imbedded in the doors and every time they opened or closed, the fluxgate heading would change about 40 degrees.

My first thought was to reposition the heading sensor away from the influence of the magnets in the doors but no matter where I could mount it there were other magnetic influences that would be just as bad.

I gave the customer 2 options. I could butcher up his nice teak laminated doors to get the magnets out or set up his AP with the doors either open or closed but whichever way he chose, the heading would only work that way. He chose to have me set it up with the doors closed as that was the way he normally ran the boat.

"Kelvin balls" is also new to me, j call them soft iron compensators only needed on steel boats. With n/s e/w standard compensators for permanent magnetism you can nearly always reduce deviation to a few degrees on a wooden or plastic boat. Joachim fr Gothenburg Sweden

ReplyDeleteAnon, thanks. The nickname "Kelvin's Balls" came about because Lord Kelvin creator of the kelvin temperature scale and many other things is also the inventor of the compass compensation system. Lord Kelvins Balls first appeared on binnacles in 1880.

ReplyDelete